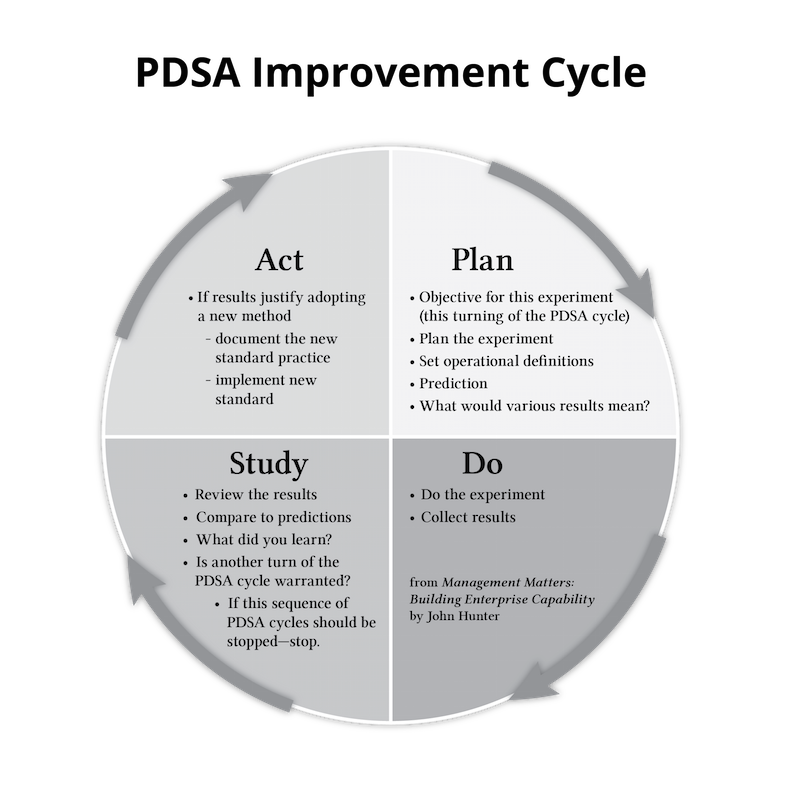

The PDSA improvement cycle was created by Walter Shewhart where Dr. Deming learned about it. An improvement process is now part of many management improvement methods (A3 for lean manufacturing, DMAIC for six sigma and many other modifications). They are fairly similar in many ways. The PDSA cycle (Plan, Do, Study, Act) has a few key pieces that are either absent in most others processes of greatly de-emphasized which is why I prefer it (A3 is my second favorite).

The PDSA cycle is a learning cycle based on experiments. When using the PDSA cycle, it is important to predict the results. This is important for several reasons but most notably due to an understanding of the theory of knowledge. We will learn much more if we write down our prediction. Otherwise we often just think (after the fact); yeah that is pretty much what I expected (even if it wasn’t). Also we often fail to think specifically enough at the start to even have a prediction. Forcing yourself to make a prediction gets you to think more carefully up front and can help you set better experiments.

An organization using PDSA well will turn the PDSA cycle several times on any topic and do so quickly. In a 3 month period turning it 5 times might be good. Often those organizations that struggle will only turn it once (if they are lucky and even reach the study stage). The biggest reason for effective PDSA cycles taking a bit longer is wanting more data than 2 weeks provides. Still it is better to turn it several times will less data – allowing yourself to learn and adjust than taking one long turn.

The plan stage may well take 80% (or even more) of the effort on the first turn of the PDSA cycle in a new series. The do stage may well take 80% of of the time (when you look at the whole process, multiple turns through the PDSA cycle) – it usually doesn’t take much effort (to just collect a bit of extra data) but it may take time for that data to be ready to collect. In the 2nd, 3rd… turns of the PDSA cycle the Plan stage often takes very little time. Basically you are just adjusting a bit from the first time and then moving forward to gather more data. Occasionally you may learn you missed some very important ideas up front; then the plan stage may again take some time (normally if you radically change your plans).

Remember to think of Do as doing-the-experiment. If you are “doing” a bunch of work (not running an experiment and collecting data) that probably isn’t “do” in the PDSA sense.

Study should not take much time. The plan should have already have laid out what data is important and an expectation of what results will be achieved and provide a good idea on next steps. Only if you are surprised (or in the not very common case that you really have no idea what should come next until you experiment) will the study phase take long.

I find Act confuses people and I believe viewing it as either 1) deciding to adjust and iterate again with another experiment or 2) adopting the change is helpful (or abandoning the experiment if it is decided that is the best option). Organizations that do PDSA well are adjusting and continuing to experiment much more than they are adopting (quick iteration is a key to successful PDSA). Maybe since it is named Act may lead people to want to adopt the change and show they are “acting.” It feels odd when the Act step is often just – “yes we should adjust and experiment again.”

The standardization process should be fairly standard itself. So adopt-the-change will mainly just be to follow that process (for example, update visual job instructions and then…).

Often the standardization process itself may include a short PDSA. Essentially a standardization PDSA may well be planned for just 1 iteration, just to test that the results are as expected. Rather than just adopting the change it may be wise to test the results work in more situations than were tested in your PDSA. This process is very situation dependent. Another option is to add a few cycles on the end of the main PDSA that expands the experiment and access the results. It essentially depends on the process to adopt improvements to processes (which is often dependent on the organization – different sites, different departments…).

It is also critical that you have an understanding of variation. Otherwise you can’t make decent decisions about what is effective and what is not.

By far the best resource for using the PDSA cycle is the Improvement Guide Handbook. If you are using the PDSA cycle to improve you definitely should have this book.

Related: How to Get a New Management Strategy, Tool or Concept Adopted – Making Better Decisions – Google: Experiment Quickly and Often

Thanks for elaborating on the PDSA cycle. I also think that Act is confusing, but when you consider Do to be “doing the experiment” as you mentioned, then Act becomes any changes to your process as a result of the experiment.

Sometimes the boundary between Do and Act is blurred in cases when the result of the experiment is to continue it indefinitely. i.e. a kaizen activity that involves rearranging a work cell to improve flow. If it works, then you leave the changes in place.

I guess the PDSA cycle becomes more natural when dealing with minor incremental changes, like process settings that can be measured.

Thanks for the post John. That provides a very nice overview as I practice this strategy.

Great blog post John. I really like how you emphasize on the multiple PDSA cycles required to get a significant improvement. Most of us just want the cycle to be “one and done” but really were just shortening then the process to PD (Plan, Do). I believe the SA (Study, Act) steps naturally lead to more cycles of the process.

I’m definitely going to share this article when I train employees on PDSA for ISO9001.

Looking forward to more blog posts!

John -There seems to be a missing link in your first sentence that is critically important to the effective use of the cycle.

As Peter Senge has suggested, Shewhart didn’t create the cycle but actually got it from John Dewey. That’s because this continuous cycle is what grounds human learning. What we label the Shewart/Deming Cycle is driven by natural human “programming” embedded both biologically and psychologically.

Once one recognizes that the capacity for this trial & error way of dealing with experiences is already extant, then organizational effectiveness strategies can focus on how to enable people to “do what comes naturally.” And in that way, both they, and the organization becomes continually more effective.

I find that this helps explain for me why in some cases, “PDSA” works while in others it doesn’t.

(There’s more about this on my “thinking differently” website)

Pingback: Richard Feynman Explains the PDSA Cycle » Curious Cat Management Improvement Blog

Pingback: Deming’s Ideas Applied in High School Education « The W. Edwards Deming Institute Blog

Pingback: The Improvement Guide « The W. Edwards Deming Institute Blog

Pingback: Testing Lesson from Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink — Hexawise

Pingback: Hallmark Building Supplies: Applying Deming as a Business Strategy « The W. Edwards Deming Institute Blog

Pingback: Resources for Using the PDSA Cycle to Improve Results » Curious Cat Management Improvement Blog

Pingback: Standard Work Instructions are Continually Improved; They are not a Barrier to Improvement « The W. Edwards Deming Institute Blog

Pingback: Predicting Results in the Planning Stage

Pingback: Transform the Management System by Experimenting, Iterating and Adopting Standard Work » Curious Cat Management Improvement Blog

Pingback: Reflections on Dr. Deming’s Hospital Notes – What Has Changed Since 1990? « The W. Edwards Deming Institute Blog

Pingback: Deming on Management: PDSA Cycle « The W. Edwards Deming Institute Blog